As we explored in our last newsletter, low back pain is overwhelmingly common, with tens of millions of Americans impacted by symptoms at this very moment. Each person’s situation is unique and the severity of these individual’s back pain varies, but most frequently experience some degree of disability or limitation that interferes with their normal way of life.

One of the many consequences of having low back pain is that it often reduces physical activity levels. Whether it’s not accepting an invitation to play a pickup game of basketball or avoiding yard work that involves lots of bending and twisting, a sizable portion of low back pain patients will notice a decrease in movement because of their condition. Unfortunately, moving less can actually increase pain levels, making it even more difficult to move and initiating a challenging cycle of pain and inactivity.

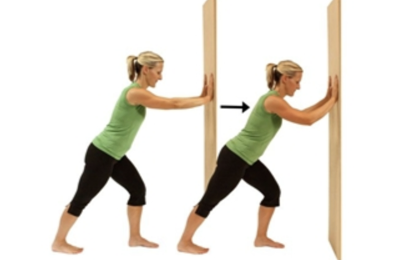

On the flip side, moving more and staying active is one of the best things you can do for your pain. Although it might seem sensible to avoid any motions that could lead to pain, the truth is that regular physical activity is crucial because it helps to keep your muscles strong and joints flexible. Exercise will also increase blood flow throughout the body and specifically to the lower back area, which may reduce stiffness and speed up the healing process.

Activating the lower back and core muscles can help with support and stability for the spine, which in effect leads to less strain and less pain. With this in mind, we present the three best strengthening exercises for your low back and hip muscles.

NOTE: before you try these or any other exercise program, please consult with your physical therapist or physician.

- Glute bridge (bridging)

- In addition to the lower back, this exercise strengthens the hamstrings, gluteal muscles (buttocks), and hip muscles; to perform this exercise:

- Lie with your back to the floor, knees bent with only your feet on the floor

- Dig your heels into the floor a bit and squeeze down on your gluteal muscles

- Lift your hips up until they are 6–8 inches off the ground and hold this position for about five seconds

- Slowly bring your hips back to the floor and give yourself about 10 seconds of rest

- Repeat 8–12 times

- The Bird Dog

- Bird Dog is a great way to learn to stabilize the low back during movements of the arms and legs; to perform:

- Get on your hands and knees and tighten your abdominal muscles

- With one leg, lift and extend it behind you while keeping your hips level; lift and hold the alternate arm out in front of you; hold for 5 seconds

- Switch to the other leg and arm. Repeat 8–12 times per side.

- For an added challenge, try lengthening the time you hold each lift

- Lying lateral leg lift

- This exercise strengthens the hip abductor muscles, which support the pelvis and can help reduce strain on the back; keeping these muscles strong can also help you maintain balance and improve stability; to perform

- Lie on one side with your legs together and lower leg slightly bent

- Bring your bellybutton into your spine to engage the core muscles

- Raise your top leg about 18 inches, keeping it straight and extended; hold the position for 5 seconds

- Repeat 10 times

- Turn onto the other side of the body and repeat, lifting the other leg

- Perform 2 sets on each side

In our next newsletter, we’ll look into the role that physical therapy can play when low back pain persists after performing these exercises and for patients that require a more hands–on approach to their condition.