Low back pain is jarringly common. About one-half of all working Americans will experience symptoms at least once every year, and roughly 31 million are affected by it at any given point in time. So if you find it appropriate to place yourself in this category, you’d have an abundance in company.

Dealing with low back pain can be troublesome and place a strain on everyday life. Typical movements like bending over to pick something off the ground or twisting your torso when looking to the side might suddenly give you pause and make you less mobile in the process. This development naturally leads to frustration and often shifts to a focus on one main question: “what’s causing this pain?”

As a result, many patients with low back pain start to place a particularly strong—and sometimes unhealthy—emphasis on obtaining a diagnosis. They usually believe that doing so will clearly explain why they are in pain and will allow the right treatments to be performed. Sadly, searching for a diagnosis for low back pain is complicated and often does not lead to the outcomes that most patients hope for. And in many cases, it can do more harm than good.

Why ‘abnormal’ is a relative term

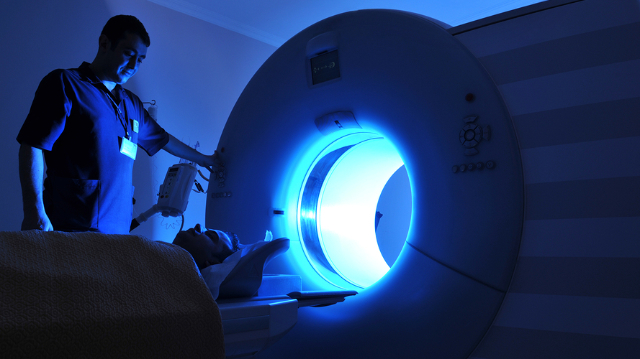

In their hunt for a diagnosis, many patients will decide to have an imaging test performed, which include X-rays, MRIs, and CT scans. These types of tests serve an integral role in diagnosing a plethora of conditions throughout the body, but when it comes to low back pain, their usefulness is not as certain. The primary issue is that an imaging test should serve as only one component of reaching a diagnosis, in addition to a detailed patient interview and thorough physical examination. But many patients—and some doctors—rely too heavily on the results of the test instead.

In addition, the results from these tests are not always as clear-cut as one might assume. Many individuals who don’t have any low back pain symptoms will have “abnormal” findings on an imaging test, while many of those with symptoms will test results that appear to be completely “normal.” To put matters in perspective, below is a brief summary of the findings from an important study that reviewed the MRIs and CT scans of more than 3,000 individuals with no signs of back pain:

- 20-year-olds: 37% had “disc degeneration” and 30% had “disc bulging”

- 50-year-olds: 80% had “disc degeneration” and 60% had “disc bulging”

- 80-year-olds: 96% had “disc degeneration” and 84% had “disc bulging”

These results show that disc degeneration and disc bulging are extremely common in most people without back pain, and the likelihood of having these findings increases significantly with age. When not explained properly and interpreted in the context of an examination and other factors, a patient with back pain may incorrectly believe that these “abnormal” findings are the same thing as a diagnosis, when they may instead be a sign of the natural aging process. The words “bulging” and “degeneration” also tend to create scary images of the spine that could further alarm patients and push them towards undergoing interventions like surgery to fix the problem, even though their results may have nothing to do with their pain.

It’s important to point out that there are several diagnoses that are extremely important and require careful medical intervention, some of which an imaging test will assist with. Spinal tumors, cauda equina syndrome, spinal infection, abdominal aneurysm, and ankylosing spondylitis are among the conditions that typically lead to severe symptoms, but none of these are very common. Two other signs that something more serious could be present are incontinence and or numbness around the groin and buttocks, and any accident that could have fractured the spine. If either of these signs accompany back pain, it’s imperative that you seek out immediate medical attention.

But in the vast majority of cases, patients with low back pain should focus more on addressing their condition with a movement-based strategy and less on obtaining a diagnosis, which is not the silver bullet they might be expecting. In our next newsletter, we’ll provide you with some strengthening exercises that you can perform to alleviate your low back pain on your own.